High Output Management for (Non-managing) Tech Leads

If you've worked in tech long enough, you'll hear praise for Andy Grove's High Output Management, oft-praised as a touchstone of technology management (Grove is often referred to as the "Father of the OKR"). A year or so ago, I got to read his book through Harrison Metal's General Management course. What can you apply from the book when you're a tech lead, and not actually a manager?

I’ve written a bit on this blog about the highs and lows of my time in engineering management. I’m a team lead nowadays - less managing, more coding, but I still think long and hard about what leadership means and looks like in the tech industry.

Re-reading the book recently made me realize that there could be a useful angle for tech leaders who aren’t in direct management, but are in leadership roles anyway. Folks in our shoes tend to work closely with first- and second-line managers. Even though Andy Grove’s advice is targeted to this group, plenty of it still applies to the lead role, and understanding the challenges and mindset of your manager compatriots will greatly increase your effectiveness as a lead.

Output Observability & Grove’s Breakfast Factory

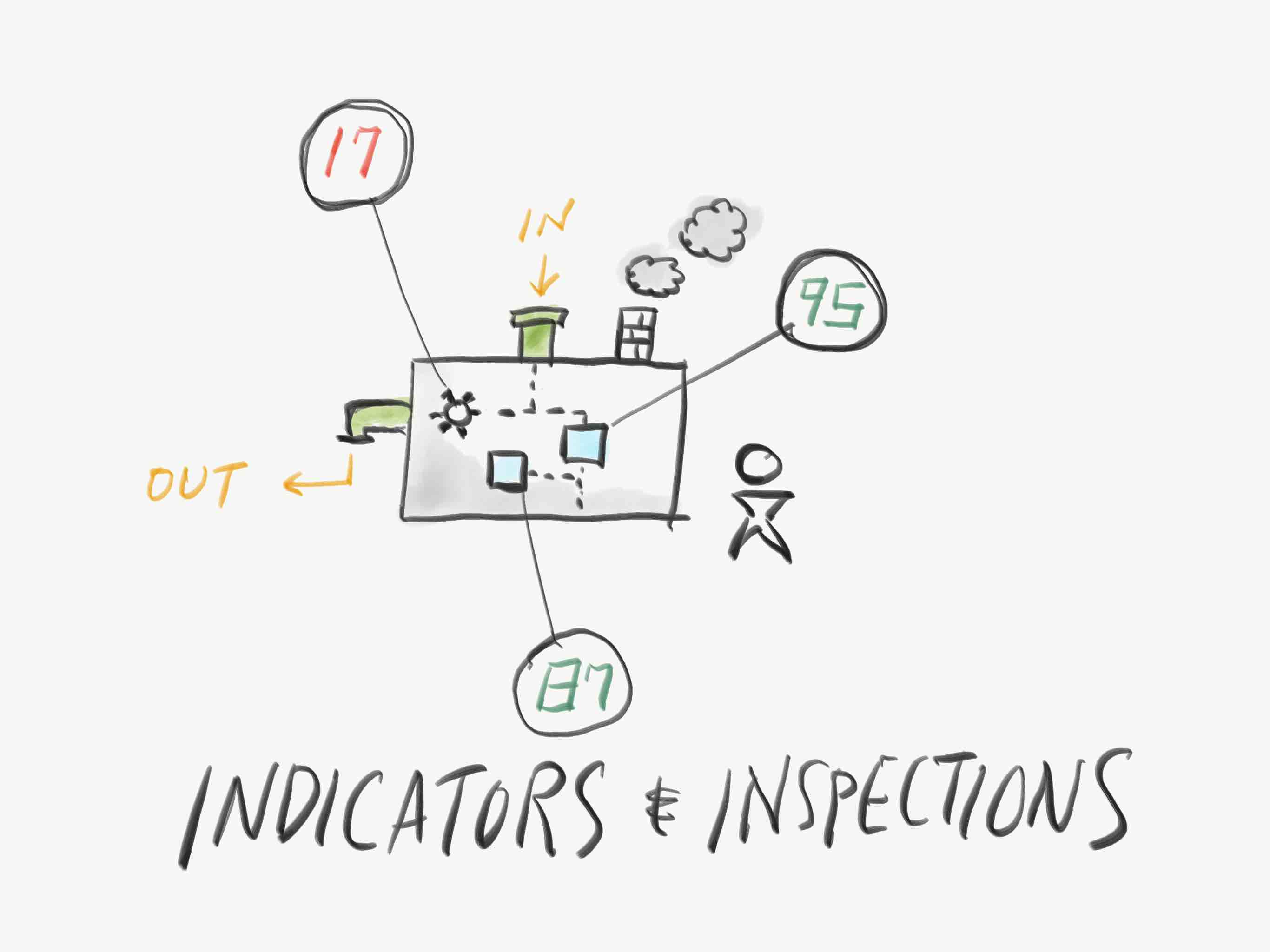

Andy Grove leads with an iconic example of running a diner, giving examples of how you might measure the output of a business flipping griddles, eggs, and waffles at a breakfast diner. To him, software production is not so different from an assembly line metaphor, and he takes the reader through a tour of his fictional diner business. In the end, he concludes that managers need to develop metrics that let them monitor the output of their own “factories” through three types of indicators: Output Indicators, Quality Indicators and In-Process Inspections.

What are the indicators your manager could be watching for?

- Output indicators: Did we ship what we committed to ship, on time? How is the velocity of the team trending, and what can we do to unblock them to go faster? What is the business impact of our software releases, and are they trending positively?

- Quality indicators: What was the defect rate of what we’re shipping? How is code quality doing overall? How is test coverage?

- In-process inspections: Provide some context and walk your management counterpart through a “batch” of output. It could be walking them through a feature that was just released, or explaining the architecture of a new, complex feature.

The takeaway for technical leads? Collaborate closely with your management counterpart to develop and contextualize these indicators. Your management counterpart may not always have the day-to-day context of what is happening, so your expertise will set them up for an accurate evaluation of team output and performance. Help explain the progress and status of the team to give the manager confidence that the team is operating to its fullest potential.

This could look like:

- Being fully invested in the OKR-setting process, making sure you’re both on the same page about the metrics most important to tracking team output.

- Shipping a live dashboard tracking key metrics, displayed on a TV monitor on the team floor.

- Weekly check-ins with an agenda going over team output metrics.

- Or even more simply - a conversation - “What do you care about seeing?” “What worries you the most about our team?” Then from there, jump to developing metrics that display progress toward a goal.

Leverage, for the Technical Lead

Much is written in the book about how a manager’s role is defined by their indirect influence on the output of the organization(s) under them. Given the scarcity of time for most managers, Grove encourages managers to seek out high-leverage activities to maximize their influence.

Oh, and one more key insight. Grove cautions his readers from confusing activity with output. Merely filling your day with low-leverage meetings may not be the best use of your time.

Technical leads have much to learn from this insight as well. What are high-leverage activities for a technical lead? What are low-leverage activities?

| High Leverage | Low Leverage |

|---|---|

| Attending an architecture review board meeting | Working on a “juicy” feature in isolation |

| Leading a backlog grooming session to make sure the work is well-defined for the next iteration or sprint. | Working on something just because the tech is cool but with low business value |

| Pairing with another developer to do knowledge transfer | Nitpicking over syntax on someone’s PR |

| Working on external documentation* | Oh, did I mention coding in isolation? |

| Performing an effective, empathetic code review | |

| Discussing tradeoffs and opportunities with other product leaders |

* Varies by org size and team composition

Relationships, Leverage, and Connective Tissue

See that? High leverage activities involve communication and coordination between teams. They often help communicate work streams, set expectations to other stakeholders, or do the plain, boring work of defining work clearly and explicitly.

Low leverage activities oftentimes happen to be the “fun stuff” - a juicy feature that happens to let you refactor your fancy system to use a new pub/sub framework, or try out a new frontend or mobile framework. The “low leverage” part comes when you, the lead, take the work yourself without bringing anyone along with you.

In other words, the leverage from a team lead comes from the strength of the connective tissue they are building within their team and between other teams.

Meetings and 1:1s

While many of us might view meetings as a necessary evil to minimize, Grove takes a high view of 1:1 meetings. I believe that the effective lead should also do the same.

Since leads often have the highest amount of day to day context to the team’s work, you can be well positioned to put the day to day in context of the strategic in 1:1 meetings with your teammates.

What do I mean by “context of the day’s activities”? If you are doing your job of directing the day’s efforts and helping coordinate the daily tasks on the team, then you have execution authority to the execution flow of the team. You know who is working on what, and what streams of work remain blocked or undone.

| What to talk about | Why |

|---|---|

| Opinions and feelings about project progress (“How is the project going?”) | You can get a read into your teammates’ heads and address morale or nagging questions |

| Career mentoring and coaching (“How can I help you grow?”) | Your unique view of the project as a peer on the project will allow you to feed your teammate advice as to how to adapt her or his skills to seek advancement. Focus on giving actionable feedback with an immediate application. |

| Real-time feedback (“How am I doing?”) | Since you are a peer doing the work along with your coworker, you can give feedback in near-real-time as it happens. That gaffe in that meeting, or a code review comment that fell flat, or the bungled feature deployment can all be discussed or addressed at your 1:1 without having too much time pass between the incident and the resolution. |

The lead doesn’t have direct managerial authority, and in many ways, that is your superpower. Your authority comes in a tactical form, and that oftentimes makes input easier to swallow (than, say, if it came from your boss). You may find that your teammates find it easier to open up to you when they find that you are a safe person to confide in (more on that in a future post).

This also makes you valuable to your managing counterpart, as they can work with you to come up with coaching strategies for new hires or underperforming teammates.

At Lyft, we have a strong culture of inter-team one-on-one meetings. I’ve used these meetings to talk teammates through interpersonal issues, provide a listening ear to discuss the purpose of different strategic initiatives, or simply talk through execution-oriented agenda items like code style and architecture patterns.

By the way, this doesn’t mean that I don’t believe that managers can do these things either! I just mean that tech leads have more natural authority that comes from their tactical involvement in the day-to-day.

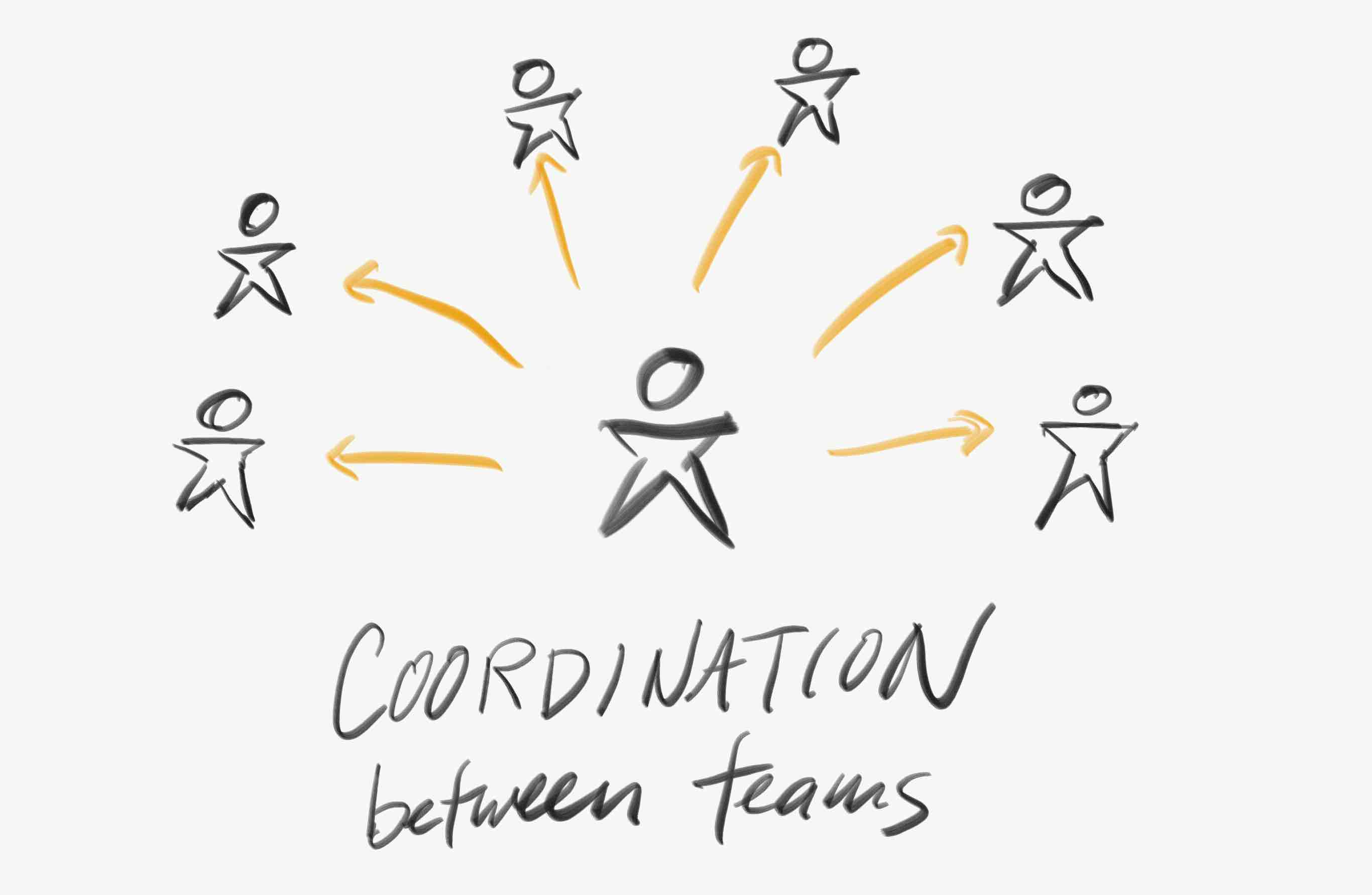

The outward-focused Operational Review meeting

Grove encourages managers to convene Operational Review meetings, whose purpose is to review the progress of an initiative or project. They can be held with a cross-team audience or within the team. The purpose of these meetings is to help leadership assess the health of a project or initiative so they can make decisions to keep it on track.

As a tech lead you may consider your role in presenting operational reviews to product or technical leadership. While your immediate management counterpart likely already has a great grasp on the status of your project, you can maximize alignment potential of communicating status clearly to cross-functional stakeholders.

Imagine a tech lead who is asked to represent the team at a monthly status meeting that convenes leaders in mid- to senior-level management who are interested in the progress on the team’s highly-visible project. Our lead may want to represent the technical execution aspect of the project, ready to answer questions like:

- How does the architecture of this project set us up for strategic success 2 years down the road?

- Are the technical debt tradeoffs we are making in this iteration addressable in the next?

- How is this team collaborating and integrating with the systems of other teams up- or downstream from the system?

The peer-level Operational Review meeting

I’m going a little off-script here since this isn’t exactly a Grove takeaway in his book, but from my experience it is just as important for the lead to demonstrate status progress to her peers - other leads or managers in other parts of the org. This reduces duplicative work, allows “aha” realizations that one team can use the tech of another team’s work - in other words, it increases leverage.

These peer reviews can take several forms. You may want to convene a cross-functional group of peers (co-leaders at your level) to communicate the status and challenges of your product surface. This can be something as simple as explaining progress on the project, presenting some architectural diagrams and summarizing with some needs and open blockers. Your audience may take time to give their perspective, to offer solutions, or to help problem solve with you.

Else, the tech lead can send out group updates to his or her peers in a shared Slack channel or email distribution. Peer cohorts can subscribe to these updates and glance through the updates periodically.

Example: At Lyft, a group of engineers in our Growth organization often gather in a Friday meeting to discuss their product areas on a monthly cadence. This group gathered represents teams from across nearly the entire product surface. Conversations may range from architecture reviews, to product presentations with open Q&A for presentations or brainstorming. The objective of the meeting is to share information that would otherwise have been contained in a silo, and find leverage points between the groups where opportunities may have been missed.

Making Decisions (as a Lead)

Grove talks about the primary responsibility of managers to make decisions. How should this work? Managers need to provide a venue to provide input, facilitate discussion, then after all inputs have been received, the manager can make a decision.

We can apply this to technical leading in two ways. First, it is important for a lead to be a decision-making partner to her management counterpart. Let’s imagine a manager needs to decide whether to make a case to senior leadership to expand headcount on the team. The technical lead can make the tactical case for doing so by explaining how the team’s output is blocked due to a key skill set being missing with specific examples of PRs, code samples, and/or specific backlog items that went unfinished or were underinvested in.

Secondly, the tech lead herself may make decisions. These decisions tend to live at the boundaries at the tactical and the strategic, and may include:

- Should we address tech debt now, or punt on it until after the big product push?

- Is there a new technology that we should be investigating now that could pay dividends in the future? For example, a new core technology (a streaming architecture, a blockchain/distributed ledger, a native mobile app) may unlock new product capabilities for the business to capitalize on.

- Are there leverage points for our team to integrate with other teams? Is there an opportunity to internally (or externally) platform-ize our technology?

Of course, these decisions do not occur in a vacuum. Like Grove suggests, our lead must be able to convene the group of experts (the team) and have the team give their feedback and opinion.

Conclusion

Tech leads reading Grove’s High Output Management get a cheat sheet into the manager’s mindset, helping their management counterparts get the clearest picture into the performance of the team.

Tech leads can also take on a manager’s mindset, using 1:1s with their teammates to develop each member. They maximize their leverage as technical leaders to build bridges between other groups within their organizations.

References:

Andy Grove: High Output Management. https://www.amazon.com/High-Output-Management-Andrew-Grove/dp/0679762884