The Product Owner Engineer - The Four Product Hats

Cool, we've got swarms of empowered ICs working on their newly ideated projects. How do you keep the team holistically moving toward the right goals, without having the superpowers of a PM on hand? You improvise and hand out some hats.

In Part 2, we built a bottom-up Idea Backlog-driven generation engine. Now we have swarms of ICs working on their own projects, the team still lacks organizing principles and a way to keep moving forward toward the right goalposts. In other words, we still need to solve the same problems that a PM would normally solve:

- Deciding what the most important (or impactful) work is to take on during that iteration.

- Reporting team progress and work output to interested stakeholders

- Managing work within an Agile process

The Four Hats

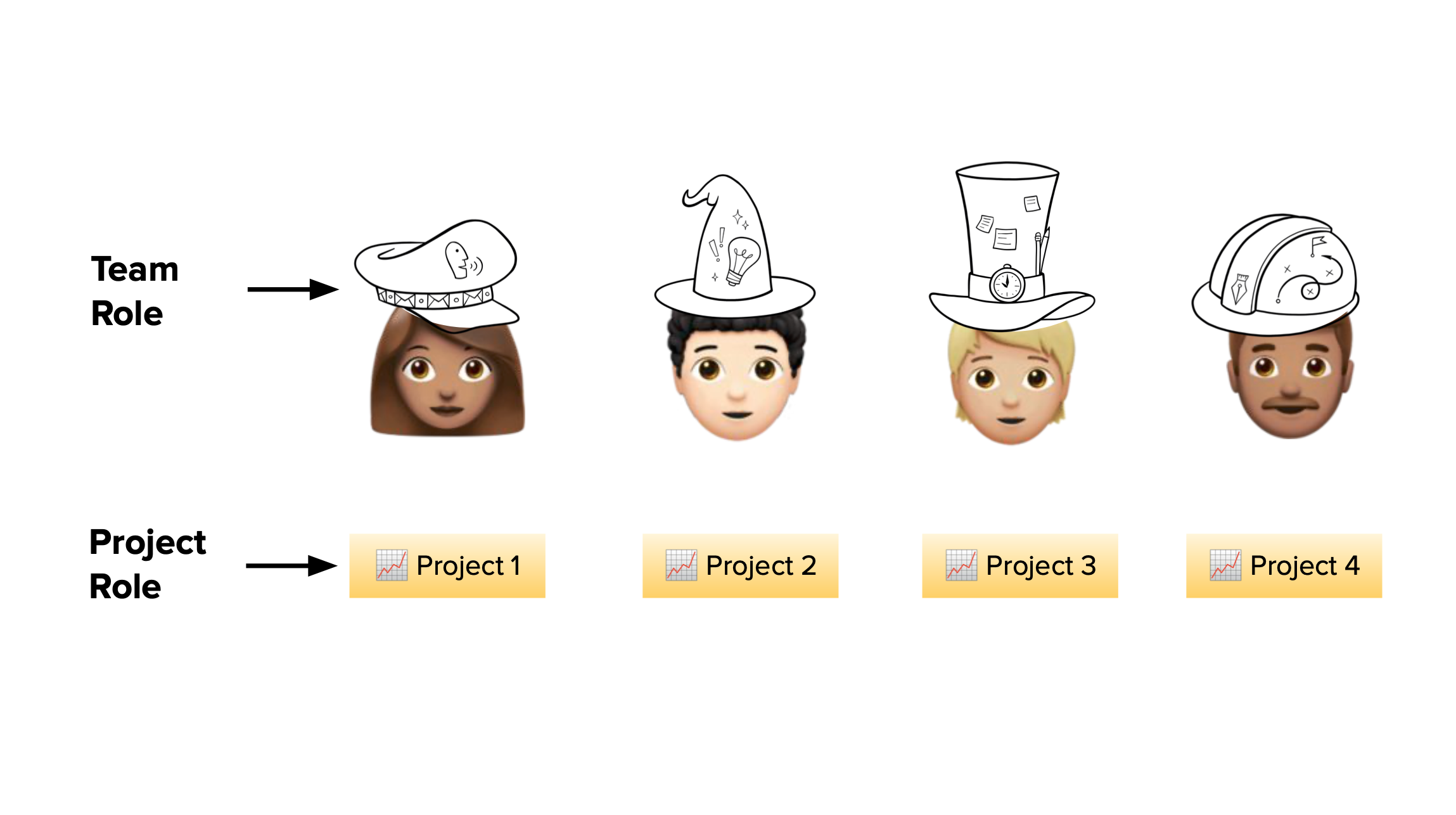

We thought about what PM’s do for teams and we broke them up into four jobs, or “hats”, which four volunteers on the team manage. It looks something like this:

In addition to taking on Project Roles, teammates also rotate through Team Roles that reflect one aspect of product ownership. Let’s go through them one by one:

The Messenger’s Job is to Inform Stakeholders

In one sentence: The Messenger ensures that necessary stakeholders are informed of team progress.

It looks like: Each week, the Messenger posts a team update to a Slack channel describing the achievements of the team that past week. The update will include relevant links to backlog items, tech specs, and experiment results. The update highlights upcoming work and current project blockers.

Messengers are responsible for staying abreast of team members’ work status, aggregating them and summarizing them for a larger audience.

Messengers may also represent the team at cross-team meetings, such as product reviews and higher-level meetings to represent the work of the team.

If the Messenger were not doing their job: Stakeholders would be unaware of the work (and the wins) that the team is accomplishing. The potential for organizational confusion and duplicate work would rise.

The Scrum Master’s job is to Do Agile™️

In one sentence: The Scrum Master facilitates our planning-oriented Agile ceremonies:

- backlog grooming

- sprint planning

- (and sometimes - standups and retros)

The Scrum Master doesn’t have any explicit decision-making powers, but ensures that these meetings run smoothly. Their laser focus is to help the team develop a beautiful set of backlog items.

It looks like: The Scrum Master works with each teammate to write well-defined user stories. This means that this individual must be well-read on Agile story-writing and understand how to facilitate sprint planning and estimation activities.

(Note - Agile purists will note that this is not technically the definition of a Scrum Master, but we liked the name and it stuck).

If the Scrum Master were not doing their job: the work necessary to develop a clean work backlog would fall through the cracks, leading to disorganization, uneven story definitions and unclear team metrics.

The Architect’s Job is to Make Prioritization Decisions

In one sentence: The Architect makes prioritization decisions for the team.

It looks like: The Architect thinks hard about the overall team roadmap, what initiatives need prioritization (and conversely, deprioritizing), and then makes the calls for the team. The Architect is likely that team member who already operates at a strategic level - most likely a more senior member of the team or someone in management.

This team member, throughout the week, makes prioritization decisions in the backlog, bringing up projects and stories that have immediate impact or urgency.

The Architect is responsible for maintaining relationships with other Product Managers in the organization to stay abreast of strategy discussions and stay in the loop with product discussions. This means that the Architect must be sure to represent the team in formal product reviews.

On my team, my manager plays the Architect, and it’s clear that their natural relationships with product and engineering leadership makes them the most qualified to play the Architect. It doesn’t mean that the Architect can’t be someone in an official management/leadership role, but it certainly makes it easier.

If the Architect slacked on the job: then the team would have no runway for new projects, or would spin their wheels trying to identify the most important work to do. The team may be unaware of broader strategy discussions, or run and chase after non-impactful projects.

The Dreamer’s Job is to Get the Idea Juices Flowing

In one sentence: The Dreamer’s job is to facilitate the Idea Generation engine.

It looks like: Our team weekly maintains a separate list of new ideas that we vet together, and the Dreamer’s job is to make sure that list of ideas is prioritized accordingly and well-defined.

In other words, the Dreamer’s job is to make sure the Idea Engine is running smoothly. They are the Scrum Master (the process facilitator) for the intake engine.

The Dreamer is constantly reminding the team to input new ideas into the engine. The Dreamer also facilitates group brainstorms and other idea-generation sessions that help the group do brainstorms.

One thing that I’ve noticed is that “idea generation” is not a natural thing unless you are deeply tuned into customer problems. The Dreamers who are most effective are those who can keep the team in tune with real customer pain points.

This might mean collaborating with a UX researcher to summarize findings for the team, or even doing a deep-dive onsite interview with a new customer. It might mean shadowing a support agent for a day to understand issues that customers face, so they can return to the team and broadcast some real challenges that need addressing.

If the Dreamer did not do their job, then the team would run out of impactful projects to implement, or would work on shallow-work that doesn’t truly solve a customer problem.

How’s it going?

We’ve been running this process for nine months now, and a few findings have emerged:

Wins

It’s very possible to operate without a PM! Months of product-owner operation have demonstrated to us that it is possible to run a bottom-up engineering team process. Our overall team output has not wavered much, despite the additional overhead of managing our PM responsibilities.

The team feels empowered to make impact - the culture of the team is very encouraging and positive. Ideas are encouraged and celebrated. People report that they feel empowered to make ideas a reality, and that the team’s culture encourages new, risky or unproven ideas.

Challenges

Lacking a seat at the table: Even though our team can operate independently, we oftentimes lose out on having a seat at the table with the rest of the PMs when they gather to formally discuss strategy and have syncs. This causes us to sometimes lose advance conversations that lead us to be a step behind emerging product strategy. This means that we must work hard to develop relationships within the PM org.

Idea Generation is unnatural: We’re still building the Idea Generation muscle into our team memory. For years, most of us have worked by having work handed to us by a PM. When given the opportunity to experiment and try out new things, we need to be in the right mindset to try that out. As a team, we are learning to understand customer pain points better so we can be nudged to experiment and try out new solutions.

Wearing a PM Hat is uncelebrated work: The additional workload of product management is a significant time commitment for our team. Depending on the role, this may take anywhere from 10% to 40% of their time. Many of our engineers (including myself) who have internalized an idea of “real work” to mean “execution” need to recalibrate our expectation of productivity to include the full lifecycle of events - from ideation to execution. As a team, we’re learning to celebrate the journey of building our PM muscles.

In conclusion

Can you really take a PM and split them up into four roles that cleanly - and divide the roles among a distributed team? Not easily. But it can be done. And when it’s done well, it leads to higher engagement and impact on the team.